Dad

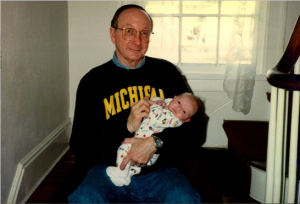

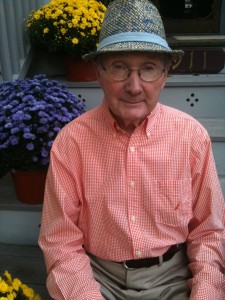

My dad passed away on January 16, 2017, from complications due to Parkinson’s disease. He was 83 years old.

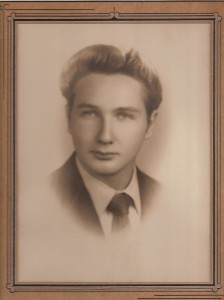

Dick Loranger

September 28, 1933 – January 16, 2017

Parkinson’s, in which a person slowly loses control of their muscular system, does not technically cause the person’s death; its effects do. Most commonly it is a dysfunctional swallow response that gets them, causing the person to aspirate food into the lungs, leading to infections or pneumonia (or in rare cases, choking deaths). In Dad’s case, his swallow response diminished to the point that he could only eat or drink with great difficulty. This resulted eventually in severe dehydration, causing further weakness, digestive blockage, and infections that landed him in hospital a few days before Christmas. He spent eighteen days mostly in ICU with doctors trying to turn him around, but ultimately he was not able to nourish himself, and just grew weaker and weaker. He’d signed a DNR, and did not want a feeding tube, a breathing tube, or defibrillation, and so finally the doctors sent him home to hospice. He spent his last eight days in his own room, comfortable, surrounded by family, and bathed in jazz music and love.

As if the disease was not enough, to some extent he was also brought to a quicker end by the ideologies of Patriarchy and Late Capitalism. Born in 1933, he was solidly in the Silent Generation, imbued early on with the importance of following tradition, obeying one’s superiors, and doing one’s part. In high school, Dad tapped into his creative side, playing tenor sax in a jazz combo, eventually landing a spot on Paul Whiteman’s TV Teen Club in Philadelphia, on which they each won wristwatches. Mom reports that Dad wore his for years. No one knows when or why he stopped playing, but after high school he worked a couple of years, got drafted smack at the end of the Korean Conflict, spent a couple more years doing deskwork for the Army in Fort Collins, then came home and went to Pennsylvania Military College for Business. And there he stayed, in business, met Mom (they went swing dancing a lot early on), and settled firmly into having a suburban family of four kids, I the first and oldest.

I said at his funeral service that I thought he’d had a tough decision choosing between jazz and the “straight” life of family and business, but I don’t really think he did. Ideologically it was a comfortable choice, and in some ways the only choice for a man so steeped in sense of duty. I do think though that the consequences of the choice, and in some sense the choice itself, never left him, as he proceeded down an increasingly difficult path to build and sustain a stable family finance. I grew up seeing him as a fairly strict, business-focused man, with no sense of his creative side. He did listen to a lot of jazz, but I had no context for it; to me it was just a kind of music that people listened to. In my teen years we were often at odds, and it didn’t surprise me at all when he objected quite strongly to my decision in and after high school to pursue a creative life as a writer. My youngest sister Leigh had the same reaction from him when she went on to study photography. But just a few years later in my mid-twenties, firmly ensconced in the poetry scene of Bohemian San Francisco and starting to get a few things published, I was surprised to have him tell me that he was envious of the life that I was living. He told me that a few times over the years, always in private, and it was much later on, after his retirement, when I had a much better sense of the history and social impact of jazz, that he admitted on a few occasions how much he regretted giving up the sax.

But these are also just decisions people make, based more on drives and personal needs than anything, though in many ways Patriarchy can be seen as a social system founded on unchecked mammalian male drives, for instance to capture and to dominate. Insofar as it can be viewed as a system of ideas, as an ideology (and I’m no critical theorist, not by far, just a sad man musing, so no doubt someone will take issue with this – and so what), Patriarchy seems to espouse a great number of prescribed behaviors which support the system itself while being detrimental to the person enacting them. For instance, the idea that a man is self-sustaining, that he does not need help, that whatever it is, he can handle it. Anyone who has friends or parents from the Silent Generation know how prevalent this is, especially when it comes to medical issues, or often even moments when they really need some help. They simply do not need a doctor – and Dad was no different. He took care of himself, and that would do just fine. Which means of course that things had to get pretty bad before anyone could drag him toward medicine. In 2008, for example, he was treated for prostate cancer (which he beat), and he chose to do so at a hospital that was more than a two hour drive from home, because they had the new focal laser therapy, which his insurance would cover. Thing was, that therapy was five days a week for eight weeks, and meant a grueling almost five hours driving per day for both him and Mom, at a time when his health was already tenuous. Even though they had many friends and relatives near the hospital, he refused to stay with anyone even one night a week to relieve the stress of driving. To him, the idea that he needed help was unthinkable. For a year or two after the treatments, he had frequent urination, which is not uncommon, but which he found embarrassing in public and inconvenient at home, so he dropped out of social life and avoided drinking water, both of which his numerous doctors told him not to do. Shortly after that, when he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s, his neurologist first off prescribed speech therapy, in order to keep his throat strong for both speaking and for swallowing. He went once or twice, but found it again embarrassing to sit in a room making strange noises, let alone home where everyone (Mom) could see and hear him. Now just because I enjoy sitting in rooms making strange noises doesn’t mean that I think anyone else should; but that’s beside the point. He let his pride or self-image allow him to disregard the strong advice of a doctor that he’d chosen himself as one of the best neurologists in the Tri-State area, and consequently he lost much of his ability to speak, and had a much greater (and more hazardous) difficulty swallowing food and water, much sooner than he might have otherwise.

I’m not trying to criticize him in any way here, I hope you realize; I’m just pointing out how strong a sway one’s early training can have on one’s decisions – how stubborn they can make you. But as well, by his later years Dad’s belief system had been kicked in the balls several times by the egregious corruptions of Late Capitalism. He grew up believing in the American Dream, insofar as that meant if you do the right things, and do your job well, you get rewarded, and you and your family will benefit. (Of course this was backed up by no small docket of white privilege, however long before that had been clearly analyzed.) But whaddaya know, that turned out not to be the case. After the company he worked his ass off at for 15+ years was dissolved in an unfriendly takeover in the mid-80’s (such a boon was Reaganomics), he watched most of his peers shucked aside while he managed to glean a “promotion”, though at a much lower pay grade than he’d otherwise have been offered. His reward for that was an incredibly shitty early pension and a triple heart bypass in the 90’s. He and Mom then opened the Cape May China Closet, a, well, mom & pop store for dishes, glasses, stemware, teapots, and the like, but it was, alas, not an era for mom & pop stores to prosper, and they closed in 2003 after ten years of scanty profits. Then what little investments he had were decimated by the artificial economic collapse of 2007, leaving him with little to enjoy in his later years, which were soon to be tossed to the wayside anyway. Dad was always a staunch Republican, so imagine my surprise when I heard him remark to a friend of mine late in ’07 regarding George W. Bush, “He’s the worse thing that’s ever happened to this country.” (I bet he’s eating his words now.) To me that signaled not so much a change of heart, but a kind of despair that his idea of this country had been wrecked. So it’s not really surprising that he would cling all the more staunchly to those principles of self that had remained intact, as he became more and more conservative regarding what control he had over his own body. He even fought Mom for a few weeks this past December over going to his local doctor as his strength and abilities seemed to be spiraling, so that finally we couldn’t get him walking at all, and we had to call the paramedics for what would be his last trip to the hospital.

In the end, he had his family, and he had his jazz. A few days before he went to hospital, I spent a couple days taking care of him to give Mom a break and a chance to get away to New York the week before Christmas. The first day went smoothly (with the help of a Visiting Angel), and the second went terribly, as his plummet had begun and I was unequipped for the tasks of cleaning and feeding him on a day when he couldn’t move or swallow. During the first day, though, we had some peaceful time together, which I’m so grateful for. I made him lunch, a grilled cheese sandwich, and we sat eating and listening to one of the cable jazz channels. This was an activity that most of us had shared with him over the last several years, one which we all enjoyed and which also kept him focused on something other than his disease. We often made it into a game of sorts, because Dad was somewhat of a jazz encyclopedia. Whenever the tune changed, the screen would show the name of the new song and the singer or bandleader, and a series of pictures and tidbits about them. Whoever was there with him would say the musician’s name out loud, and Dad would respond with a few interesting facts about their lives, or maybe a story about going to hear them, or a friend of a friend who knew them, or the like. Toward the end, he could barely speak, and it was often impossible to understand what he was saying, but we’d still play this game with him, because we knew it gave him some satisfaction. So on this day I was doing just that. At some point when the tune changed, and I said the name of the singer (I think it was Marilyn Moore), not paying much more attention than that, Dad said a couple sentences about her in an absolutely clear voice, his old voice that I hadn’t heard for years. I startled and looked up, and he was sitting upright in his chair, munching on his grilled cheese with no difficulty, with no shaking hands or head, seeming not to notice what was happening. And then, in a few seconds, it disappeared, his back hunched, his hands started shaking, he made a long, hard swallow of the little bit of sandwich he’d been chewing, and he spoke a few unintelligible words. I was breathless. I have no idea what happened, or how, but I do know that I was given a gift, a moment that I’ll never forget.

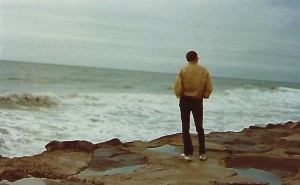

During his last days, home in hospice, we all sat around his bed, in silence, or talking to him, remembering, telling stories, laughing, crying. Each of us at times was in there alone, having our personal talks with him. Mostly I spoke with him about how glad I was that he was finally going to get out of that bed and go on a road trip with his buddies, go to hear some of the jazz greats play, to go dancing to them, and toward the end, that he was getting ready to go to the beach, which he loved. Dad, fuck the ideologies and the bullshit of this world. You made it to the beach. Now it’s time to go out dancing.

Sincerely,

Richard